Creating a Retail Multiverse: The Case of KARE ́s City Studio

1 - Introduction

Stationary retail has come under increasing pressure. Enhanced online shopping platforms, swift logistics, and a consumer demographic that dedicates a substantial portion of their time to the internet are all contributing to the growing dominance of online retailing. This trend even applies to products that were traditionally believed to be exclusively sold in physical retail stores. The ramifications of this shift are apparent in numerous cities, where empty downtown areas and vanishing retail establishments increasingly define the urban scenery. The progression of this phenomenon has been accelerated by the lockdown measures implemented due to the COVID-19 pandemic. And as if this was not enough, the next revolution is already on the horizon with tech- nologies like augmented reality and the metaverse (Sarstedt, Imschloss & Adler, 2023).

This is the situation that rpc – The Retail Performance Company, a major management consultancy specialized in customer journey design, faced when planning KARE’s new flagship city studio in downtown Munich. KARE is a Munich-based company that sells extraordinary furniture and creative accessories to consumers with high demands on design who live an extravagant lifestyle. To overcome the challenges of the current retail market, rpc decided to create an experience space, inspired by the fluidity of high-end fashion that focuses on lifestyle. Specific emphasis was put on visual stimuli that arouse curiosity and appeal to the customers’ imagination, while aligning with the KARE brand’s image dimensions.

In this article, we document the major cornerstones of rpc’s concept, which considers some of the latest academic research on visual design. The concept was honored with the BrandEx Award 2023 in silver in the Best Store Concept category (BrandEx, 2023), particularly because of its use of novel retail elements that aim to create experiential touchpoints for KARE customers. Drawing on the most recent research in the field, we will then describe how to potentially extend the concept by also taking sound and scent into account. We argue that assuming such a multisensory perspective on retail design is an important aspect of contemporary retailing and describe the retail multiverse as an important framework in this regard.

Abstract

Um gegenüber dem Onlinehandel bestehen zu können, konzentrieren sich stationäre Einzelhändler zunehmend auf die Schaffung von Erlebnisräumen, die alle Sinne der Kunden ansprechen. In dieser Fallstudie beschreiben wir die Eckpfeiler eines preis- gekrönten Konzepts, das rpc – The Retail Performance Company bei der Neugestaltung des Flagship City Studios von KARE, einem beliebten Möbelhändler, umgesetzt hat. Wir beschreiben, wie das Konzept durch die Gestaltung der Duft- und Soundlandschaft passend erweitert werden kann. Abschließend stellen wir das Einzelhandels-Multiversum als einen wichtigen Rahmen für die Schaffung einzigartiger Kundenerlebnisse im modernen Einzelhandel vor.

Keywords: #Kundenerlebnis #Multisensorisches Marketing #Multiversum #Einzelhandel #Shopping

2 - KARE’s city studio. A scenography in three acts

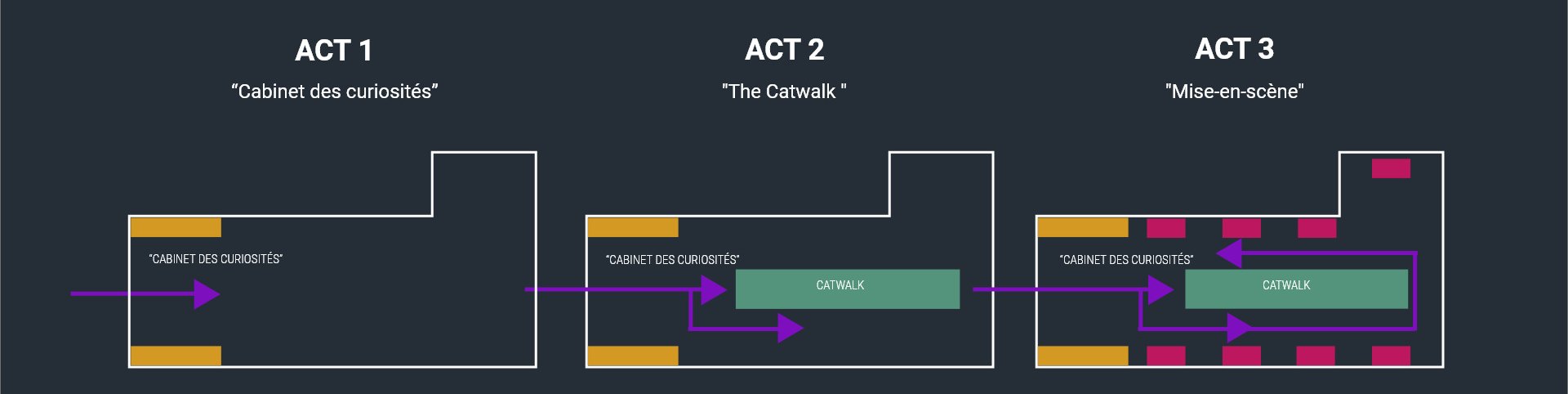

Ron Johnson, the former VP for retail at Ap- ple once said, “A store has got to be much more than a place to acquire merchandise. It’s got to help people enrich their lives. If the store just fulfills a specific product need, it’s not creating new types of value for the consumer. It’s transacting. Any website can do that” (Johnson, 2011, 80). In line with this notion and taking into account the nontraditional expectations of the KARE brand’s customers, rpc designed a furniture showroom inspired by the concept of spatial scenography. As part of this scenography, spatial design elements were used to turn the store into a theater stage, structured around three acts that takes customers on a narrative journey: “Cabinet des curiosités,” “the cat- walk,” and “mise-en-scène” (> Figure 1).

The first act (“cabinet des curiosités”), situated at the store entrance, sought to grab the attention of consumers approaching the store. Lifestyle arrangements in ceiling-high product shelves immerse customers in the world of accessories that are being multiplied by a reflective ceiling (> Figure 2). This architectural element impacts customers’ spatial perceptions, luring them to proceed further into the store.

As the customers continue their journey into the center of the store, they arrive at the second act (“the catwalk”). The catwalk is characterized by a large space in the center of the showroom and allows KARE to curate products as fashion pieces. The space offers much flexibility in that the company can continuously change accessories and furni- ture styles that match seasonal themes. The catwalk can also be used for exclusive events like fashion shows or dinner events to boost brand experience among high-profile customers (> Figure 3).

The catwalk is surrounded by various lifestyle arrangements of furniture pieces that reflect the third act (“mise-en-scène”). These displays showcase possible furniture and accessory combinations designed to reduce the customers’ level of abstraction. The furniture is being staged as a home “look and feel.” Here, the KARE team can seamlessly blend promotion with aesthetics, effectively streaming the brand’s lates products into social media channels (> Figure 4).

Figure 1: Spatial store design in three acts

Additional design elements supported the scenographic approach. For example, matching corresponding research in con- sumer psychology (Reynolds-McIllnay, Morrin & Nordfält, 2017), rpc chose dark background colors to increase the color contrast between the products and their surroundings.

Figure 2: Cabinet des curiosités

That is, the combination of dark colors and bright spotlights stimulate customers’ interest and highlight the colorful products, thereby emphasizing their storytelling role in the overall retail concept. The stage feeling is further emphasized by the use of mirrors and other reflecting material throughout the store. For example, mirrors on the entrance’s ceiling create stimulating visual effects that simultaneously highlight products and the entering customer. This visual multiplication creates a visual “wow” effect for KARE customers at the entrance of the retail space.

The seasonal themes are further emphasized by video content shown on two large screens placed at the entrance and at the back of the store. This mixed media experience is supported by touchscreens inside the store that allow customers to view social media showreels from other KARE stores around the world. The screens also provide a direct gateway for customers to access the company’s online shop, thereby allowing for the seamless placement of orders.

Figure 3: The catwalk

Jointly, the design elements create a flexible retail space with designated areas like “the catwalk,” which act as stages for multifaceted customer experiences that are further supported by visual elements like color schemes and video displays. All these elements were implemented in close collaboration with KARE’s management, taking the staff’s feedback into account.

Customer reactions toward the showroom design have been very positive as evidenced in customer feedback collected inside the store and voiced on social media. The city studio also positively contributed to KARE’s brand awareness. For example, due to the mirrored ceiling at the entrance and the overall customer journey, the store has become an attraction for passersby and generated a significant organic share on social media.

3 - The next level:

Creating a multisensory experience space

rpc’s concept emphasized architectural and visual elements in an effort to create experiential touchpoints for KARE customers. Visual impressions are often available before those of the other senses, for example, due to the fact that one may be outside the range of acoustic or olfactory signals. Therefore, the retail environment design is an important driver of KARE’s success by guiding consumer behavior and contributing to a generally pleasant atmosphere (Sarstedt et al., 2023).

However, experience in a physical retailing space goes well beyond visual stimuli. All of our senses are constantly absorbing information, processing it, and continuously combining it to gain an overall impression. Two other stimuli that KARE can easily influence, but which were initially not part of rpc’s concept, are sound and scent. In the following, we will discuss how the company could further enhance customer experience by actively managing the soundscape and scentscape, while also taking into account the interaction between the various stimuli. When implementing corresponding stimuli, KARE needs to establish sensory congruence in order to realize their full potential (Sarstedt et al., 2023).

Figure 4: Mise-en-scéne

3.1 - Soundscape

After more than 40 years of research on the utilization of music in retail settings (Felser & Hehn, 2021), researchers concur that mu- sic yields favorable outcomes at the point of sale (POS). Through a comprehensive analysis of 25 studies encompassing various genres of music, Roschk, Loureiro and Breitsohl (2017) demonstrate that music exerts a positive influence on consumers’ shopping experiences and purchasing behaviors. This effect is particularly pronounced during week-days where consumers are in a state of high- er mental depletion, which fosters more intuitive, automatic processing and makes them more susceptible to rely on music’s affective influence (Ahlbom et al., 2022).

KARE’s brand image and the visual design elements offer guidance as to which music to play in the retail space. While individual musical preferences are very complex, re- search has shown that extroverts typically prefer more contemporary, dynamic, and rhythmic styles of music such as electronic, rap, or hip-hop (Greenberg et al. 2022). This music type would also emphasize the theatric character and underline the catwalk (>Figure 3) as a central design element.

An important consideration in the choice of an adequate playlist relates to the music’s tempo, measured in beats per minute (bpm). While early research has shown that customers spend more time and money in a retail environment when slow music is being played (Milliman, 1982), more recent re- search demonstrates that music tempo interacts with consumers’ perceived crowdedness of the retail space. Specifically, analyzing more than 40,000 shopping carts across six European retail stores, Knoeferle, Paus and Vossen (2017) find that when the sales floor is perceived as crowded, fast music (≥107 bpm) compared to slow music (≤82 bpm) leads to an increase in the average expenditure per customer. This result suggests that the use of fast music attenuates the negative effect of crowding, which normally elicits negative arousal and reduces customers’ buying mood. These results suggest that KARE should play faster music on the weekends (compared to weekdays) when the store is typically busier.

This effect can further be accentuated by variations in music volume (e.g., Guéguen & Petr, 2006). Playing music at a higher volume (88 dB) will make consumers move through the store at a faster pace compared to when the music volume is at a normal level (72 dB). KARE should consider this effect by playing music at a lower volume during weekdays in order to motivate customers to linger longer.

Music could also be varied to match the seasonal themes featured in the store. Imschloss and Kuehnl (2019) show that consumers perceive products (e.g., towels) as haptical- ly softer when they listen to music of high (vs. low) music softness (i.e., music with soft vs. hard instrumentation, slow vs. fast tempo, few vs. many variations in tempo or tones, etc.) during product evaluation. For KARE, this transfer of the auditory perception of softness to the haptic perception of softness is particularly relevant for blankets and pillows since haptic softness is a central criterion for such products (Heidel & Hof- mann, 2011).

When implementing sound concepts, KARE needs to be aware that music tastes differ. For example, when Daunfeldt et al. (2021) let staff choose the type of in-store music to be played, sales plummeted by 6 percent. While this issue could be approached by first talking to the staff and finding compromises in terms of, for example, music selection and volume, some customers may react adversely to any type of music exposure.

3.2 - Scentscape

Companies like Abercrombie & Fitch and Anne Fontaine have routinely used ambient scents in their retail environments (Girard et al., 2019; Sarstedt et al., 2023). This is not surprising since research has long established that ambient scents offer a means for creating a pleasant atmosphere and effectively communicating a brand image. For example, Roschk and Hosseinpour’s (2020) meta-analysis shows that the presence (vs. absence) of an ambient scent may yield a 3 percent increase in sales for an average set- ting. However, when the scent perfectly matches the retail environment and target group, this may increase sales by up to 23 percent, while a mismatch may decrease sales by up to 17 percent. These effects also work long-term in that ambient scents positively impact consumer perceptions when they are repeatedly exposed to a pleasant ambient scent over a longer period of time – even if the scent intensity is so low that few consumers notice it (Girard et al., 2019).

How could an ambient scent be structured in the case of KARE? The scenographic character of the retail space generally calls for the use of activating refreshing scents, such as orange, melon, or lemon. Depending on the thematic focus, however, KARE could vary the scentscape seasonally by using relaxing scents such as chamomile, lavender, or rosewood (e.g., during the wintertime).

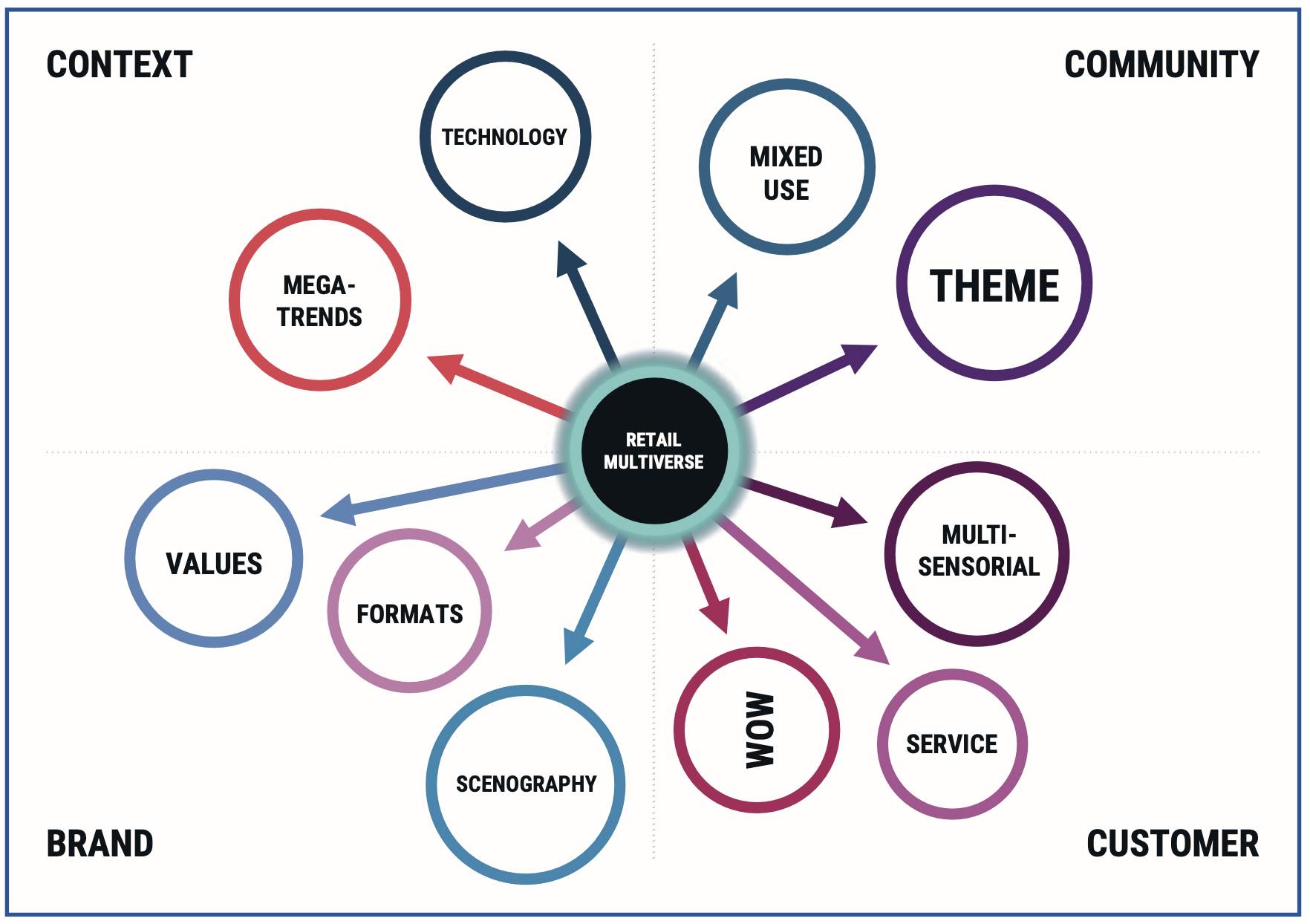

Figure 5: The retail multiverse framework

A means to simplify the choice would be to systematically vary the scent intensity to evoke activation or relaxation. A lemon scent, for example, only has an activating effect if it is very intense and, conversely, tends to promote relaxation when its intensity is low (Baccarani et al., 2021). In general, scents are more likely to develop their effect if they are used subtly. If a scent is too intense, consumers need to make a greater cognitive effort to process it, which might have a negative impact on their behavior. Even if they do not perceive the scent as un- pleasant as such, its intensity could result in irritation (Smeets & Dijksterhuis, 2014).

Another dimension on which KARE could differentiate the scentscape would be on the grounds of cold and warm scents. Cool scents, such as mint or eucalyptus, cause consumers to perceive the retail environment as physically colder than it actually is. Conversely, warm scents, such as cinnamon or caramel, have the opposite effect. Several studies have shown that these temperature perceptions lead to the purchase of symbolically warm or cold products. If a room is perceived as warm, consumers are tempted to symbolically induce cold by purchasing luxury products and premium brands, which they often view as symbolically cold (Lichters, Adler & Sarstedt, 2020).

4 - Moving towards a holistic understanding of retailing

Stationary retail is currently experiencing the most significant transformation in its history, as an increasing share of business moves into the online world with its ability to process orders 24/7 from anywhere, easy navigation, and fast delivery, sometimes within minutes. Retailers are facing paradigm shifts in that they need to offer services and experiences to different customers at different times, while the respective customer journey can be completely different. This challenge is no longer onedimensional, but multifaceted. In order to prevail in such a landscape, retailers must follow a holistic approach by reinterpreting spatial experiences and digital shopping conditions.

4.1 - The retail multiverse framework

To implement such a holistic retailing approach, companies may draw on the multi- verse framework shown in >Figure 5. One of the key elements of the retail multiverse framework is its emphasis of the interface between the brand and the customer. Specifically, the interface not only communicates the brand’s values, but also incorporates megatrends to explore a broader social context that potentially affects the brand and evolving consumer needs. This broader social context is then applied to the surrounding community of the retail space, as “not only is shopping melting into everything, but everything is melting into shopping” (Leong, 2001, 129). With reference to KARE, the store’s architecture is designed to transform the retail space into an event location in the evening hours, allowing for a club-like atmosphere (“mixed use” and “theme” in >Figure 5). At the same time, the concept meets the challenges of an increasing fusion of offline and online retailing by allowing KARE customers to seamlessly place orders online and share contents via social media (“technology” in >Figure 5).

To summarize, the framework fosters a more relational understanding of retail, being at the “crossroads of flows and events and an inevitable space of transformation on an always shifting ground” (Escobar, 2018, 38). As the retail space is continuous metamorphosis – a space of response, dynamism, ethical consumption, simplicity, and flexibility – it is important for retailers like KARE to extensively explore these vectors in order to build a pool of options that can be flexibly incorporated into the retail concept and its further curation.

4.2 - Multisensory experience as a powerful ingredient of the retail multiverse

One important building block of the multi- verse framework is the creation of a retail space that appeals to all senses. Strategically designing visual, auditory, and olfactory stimuli has vast potential to improve consumers’ shopping experience and their perceptions of products and services (Motoki, Marks & Velasco, 2023). When implementing such stimuli, managers need to be aware that consumers inevitably perceive retail environments and products in a multisensory way (i.e., simultaneously with all their senses). The presence of one sensory stimulus (e.g., scent) can influence how consumers react to another stimulus (e.g., music). Specifically, stimuli that appeal to different sensory modalities reinforce or complement one another, thereby influencing the perception and evaluation of the retail environment, the retailer, individual products, or even brands (Helmefalk & Hultén, 2017). For example, consumers associate ambient scents with specific colors (e.g., lavender scent with purple, light blue, and green) and audio tones with spatial positions such as shelf positions (e.g., high tones with high locations) – see Motoki et al. (2023) for an overview. Hence, combining a scent with specific background music can lead to an enhanced shopping experience compared to using scent or music in isolation – or, in the worst case, diminish it.

The concept of the retail multiverse, however, extends beyond the creation of a pleasant retail atmosphere. Flexible concepts are needed to ensure that shopping locations combine competent advice, service, and quality of stay – across all media and platforms. Such concepts see responsibility and sustainability not only as part of a marketing campaign, but consider co-creation, local responsibility, and transparency as integral elements of modern retailing.

Management-Takeaway

Tying in with the retail multiverse frame- work’s dimensions, the KARE case showcases how retailers may combine architectural and visual elements in a scenographic approach to engage in spatial storytelling. Visual stimuli arouse curiosity and appeal to the customers’ imagination, while aligning with the KARE brand’s image dimensions. The case study also highlights the potentials of extending this concept to other sensory dimensions such as ambient scents and sound.

References

- Ahlbom, C.-P., Roggeveen, A. L., Grewal, D., & Nordfält, J. (2022). Understanding how music influences shopping on weekdays and weekends. Journal of Marketing Research. Advance online publication.

- Baccarani, A., Brand, G., Dacremont, C., Valentin, D., & Brochard, R. (2021). The influence of stimulus concentra- tion and odor intensity on relaxing and stimulating per- ceived properties of odors. Food Quality and Preference, 87, 104030.

- BrandEx (2023). BrandEx Award 2023 würdigt Kreativleistungen: Gold, Silber und Bronze für die Kreativleistungen der Branche (Pressemitteilung). Abruf von https://brand-ex.org/brandex-award-2023-wuerdigt- kreativleistungen/.

- Daunfeldt, S.-O., Moradi, J., Rudholm, N., & Öberg, C. (2021). Effects of employees’ opportunities to influence in- store music on sales: Evidence from a field experiment. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59, 102417.

- Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

- Felser, G., & Hehn, P. (2021). Von Bottom-up zu Top-down in der Ladenumwelt: Multisensualität am Beispiel von Hintergrundmusik. In M. Gunnar, M. Schweizer, & C. Oriet (eds.), Multisensorik im stationären Handel Grundlagen und Praxis der kundenzentrierten Filialgestaltung (pp. 65-87). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

- Girard, A., Lichters, M., Sarstedt, M., & Biswas, D. (2019). Short- and long-term effects of nonconsciously processed ambient scents in a servicescape: Findings from two field experiments. Journal of Service Research, 22(4), 440-455.

- Greenberg, D. M., Wride, S. J., Snowden, D. A., Spathis, D., Potter, J., & Rentfrow, P. J. (2022). Universals and varia- tions in musical preferences: A study of preferential reactions to Western music in 53 countries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 122(2), 286-309.

- Guéguen, N., & Petr, C. (2006). Odors and consumer behav- ior in a restaurant. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 25(2), 335-339.

- Heidel, B., & Hofmann, A. (2011). Der Einfluss des Härtegrades und der Verprobung von Produkten auf die Bewertung von Verpackungen, Marketing: ZFP – Journal of Research and Management, 33(4), 263-277.

- Helmefalk, M., & Hultén, B. (2017). Multi-sensory congruent cues in designing retail store atmosphere: Effects on shop- pers’ emotions and purchase behavior. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 38, 1-11.

- Imschloss, M., & Kuehnl, C. (2019). Feel the music! Exploring the cross-modal correspondence between music and hap- tic perceptions of softness. Journal of Retailing, 95(4), 158-169.

- Johnson, R. (2011). Retail isn’t broken. Stores are. Harvard Business Review, 89(12), 78-82.

- Knoeferle, K. M., Paus, V. C., & Vossen, A. (2017). An upbeat crowd: Fast in-store music alleviates negative effects of high social density on customers’ spending. Journal of Retailing, 93(4), 541-549.

- Leong, S. T. (2001). ...And then there was shopping. In C. J. Chung, J. Inaba, R. Koolhaas, & S. T. Leong (eds.), Project on the City 2: Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping (pp. 129-135). Cologne: Taschen.

- Lichters, M., Adler, S., & Sarstedt, M. (2020). Warm ambient scents nudge consumers to favor premium brands and right-wing parties. Marketing ZFP, 42(4), 22-34.

- Milliman, R. E. (1982). Using background music to affect the behavior of supermarket shoppers. Journal of Marketing, 46(3), 86-91.

- Motoki, K., Marks, L. E., & Velasco, C. (2023). Reflections on cross-modal correspondences: Current understanding and issues for future research. Multisensory Research, Advance online publication.

- Reynolds-McIlnay, R., Morrin, M., & Nordfält, J. (2017). How product–environment brightness contrast and product dis- array impact consumer choice in retail environments. Journal of Retailing, 93(3), 266-282.

- Roschk, H., & Hosseinpour, M. (2020). Pleasant ambient scents: A meta-analysis of customer responses and situa- tional contingencies. Journal of Marketing, 84(1), 125-145.

- Roschk, H., Loureiro, S. M. C., & Breitsohl, J. (2017). Calibrating 30 years of experimental research: A meta- analysis of the atmospheric effects of music, scent, and color. Journal of Retailing, 93(2), 228-240.

- Sarstedt, M., Imschloss, M., & Adler, S. (2023). Multisensory Design of Retail Environments. Vision, Sound, and Scent. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Smeets, M. A. M., & Dijksterhuis, G. B. (2014). Smelly primes – when olfactory primes do or do not work. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 96.

DOWNLOAD THE ARTICLE!

Contact us and we send you the complete Article as PDF.

We respect your privacy. For more information please read our privacy policy.